Caring for Patients on the Autism Spectrum

Caring for Patients on the Autism Spectrum

Overview

There is great heterogeneity amongst individual patients on the autism spectrum. We have created the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool to help your patients or their supporters give you individualized information about how being on the autism spectrum affects their healthcare, and what strategies and accommodations may facilitate care.

The following section describes some of the underlying issues that may necessitate special strategies and accommodations for patients on the autism spectrum.

This information, and other information about adults and ASD, can also be found in our paper Nicolaidis, C., Kripke, C.C., Raymaker, D.M. (2014) Primary Care for Adults on the Autism Spectrum Medical Clinics of North America. 98;1169-1191. download Medical Clinics paper

Back to TopCommunication and Interaction

Potential for false assumptions about communication skills

Individuals on the autism spectrum, by definition, have atypical communication. There is great heterogeneity between patients in regards to communication strengths, challenges, and styles. An individual patient's ability to communicate may vary greatly between modes of communication (e.g. spoken vs. written language). There may be large differences in receptive vs. expressive communication. For example, someone may understand spoken language, but not be able to speak, or may speak fluently, but not be able to process auditory information accurately. There may also be large variations in communication in an individual patient from one time to the next, depending on the environment, medical illness, or other stressors. For example, a patient who speaks fluently during a normal visit may not be able to use speech effectively in an emergency or in an over-stimulating environment. Similarly, a patient may be able to communicate via speech in-person, but may not be able to process spoken language over the telephone.

Understanding a patient's communication needs, strengths, and preferences is very important. Patients on the autism spectrum attribute many failed healthcare interactions to providers' assumptions, misunderstanding of their strengths or challenges, or the fact that the communication did not occur using the most effective method.

Do not assume that a patient cannot understand healthcare information or communicate with you when they do not speak fluently. Similarly, do not assume that a patient who speaks fluently or with an advanced vocabulary doesn't have significant communication difficulties.

TIPS

Try to obtain individualized information (e.g. via the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool) from patients or supporters about the following.

- Patient's ability to understand spoken language.

- Patient's ability to speak.

- Patient's ability to read and write.

- Patient's use of alternative and augmentative communication (AAC). AAC may include picture-based systems (e.g. picture boards), text-based systems (e.g. text-to-speech programs), sign language, or other signs or behaviors. They may be stand-alone devices, programs on computers, tablets, smartphones, or informal systems (e.g., picture cards, notes on a piece of paper).

- Patient's preferred mode of communication.

- Patient's ability to use the telephone for between-visit communications (and more effective alternatives if telephone communication is not effective).

- Degree to which communication normally varies based on environmental factors or stress.

Attempt to use the most effective communication mode, even if it means altering your usual interview style. For example, depending on patients' needs, you may wish to have patients write or pre-record information, encourage them to use communication devices during visits, or communicate with them via electronic mail or other forms of secure messaging.

Literal and precise language

It is common for individuals on the autism spectrum to take language literally.

It is also common for individuals on the autism spectrum to require very precise language. This often becomes a concern when providers offer relatively vague information or ask patients broad, open-ended questions.

Patients may also experience anxiety because they do not know how to answer a question with complete accuracy. For example, if a provider asks, "Do you ever have chest pain?" a patient may feel that they need to think back to every day of their life to make sure he has never felt a pain in his chest. Or they may not be able to answer how frequently something happens because the symptom is not constant.

Strategies or accommodations to address the need for precision may vary by patient. For example, although some patients may need providers to use simple words and short sentences, other patients may find longer sentences or advanced vocabulary easier to understand, because it may enable the provider to be more precise.

TIPS

It is best to obtain information (e.g. via the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool) about your patient's specific preferences. In general, it is often helpful to do the following.

- Be very concrete and specific.

- Avoid figurative expressions and figures of speech.

- Avoid broad questions. In some cases you may need to ask mostly closed-ended questions or even only ones that patients can answer with "yes" or "no". In other cases, patients may be able to answer open-ended questions if you provide them with specific instructions or examples of the type of information that you seek.

- Show patients lists of symptoms from which to choose.

- Give examples of the types of things people may experience, and have the patient tell you if they also experiences them.

- Remind patients that it is OK if they do not know the answers to questions or are not exact in their answers.

- Give patients very direct and concrete examples when discussing your assessment and plan.

- Direct patients to detailed information or resources about their health conditions and treatment options.

Non-verbal communication

Patients may have difficulty understanding tone of voice, facial expressions, or body language. They may inadvertently seem rude due to their atypical body language or facial expressions (potentially in addition to their use of very direct language).

Individuals on the autism spectrum often avoid eye contact. Do not force a patient to make eye contact, because it may be uncomfortable or may hinder their ability to communicate effectively.

TIPS

Patients may make repetitive motions, also called "stimming". Examples include hand flapping, rocking, or pacing. Stimming may be an effective coping mechanism, especially during times of stress such as medical visits. Do not assume that a patient is distracted or inattentive just because they are fidgeting, making repetitive movements, or avoiding eye contact with you.

Processing speed and real-time communication

Many individuals on the autism spectrum have difficulty processing information quickly or communicating in real time.

Processing speed may interfere with healthcare communications in multiple ways. Patients report not being able to process language or information quickly enough to respond to questions or make healthcare decisions. They also may not be able to process sensory stimuli rapidly. For example, during a physical examination, a patient may not be able to indicate that an area is tender before the provider has started palpating a different area.

TIPS

Potential Accommodations Related to Processing Speed:

- Give patients time to process what has been said or to answer questions. Check to make sure they are ready to move on.

- Give patients extra time to process things they need to see, hear, or feel before they respond.

- If possible, schedule longer appointments.

- Encourage patients to prepare notes in advance about what they want to discuss. Carefully read any notes that patients bring to the visit. A variety of templates are available to help patients prepare for visits.

- Write down important information or instructions, so that patients can review them later.

- If appropriate, direct patients to detailed information or resources about their health conditions, so that they can review these outside of the appointment.

- If necessary, give patients time to make a decision and communicate the decision at a later time. It may be possible to see another patient and then return to finish a visit with the original patient, or it may be best to schedule a follow-up visit.

Sensory Issues

Individuals on the autism spectrum commonly have atypical sensory processing. This may take the form of increased or decreased sensitivity to sounds, lights, smells, touch, or taste. They may have great difficulty filtering out background noise, processing information in over-stimulating environments, or processing more than one sensation at a time.

Sensory issues can have many important effects on healthcare interactions. Patients describe many instances where sensory issues interfered with effective healthcare.

TIPS

The following are examples of accommodations or strategies that may be helpful for some patients, depending on their sensory processing. It is best to obtain individualized information (e.g. via the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool).

- Use natural light, turn off fluorescent lights if possible, or make the lighting dim.

- Try to see the patient in a quiet room.

- Have only one person talk at a time, and try not to talk to the patient while other noises are present.

- Avoid unnecessarily touching the patient (for example, to express concern).

- Warn the patient before you touch him or her. (See section on physical examinations for additional information.)

- Encourage patient or supporters to bring objects to reduce or increase sensory stimuli. Examples may include headphones to block noise, sunglasses or hats to block light, or sensory toys such as stress balls, gum, spinning tops, or soft fabric.

Body Awareness, Pain, and Sensory Processing

Many patients on the autism spectrum experience a variety of challenges related to limited body awareness. Examples include difficulty discriminating abnormal from normal body sensations; difficulty pinpointing the location of a symptom; difficulty characterizing the quality of a sensation; particularly high or low pain thresholds; and difficulty recognizing normal stimuli such as hunger or the need to urinate. Patients often describe situations where issues related to body awareness caused providers to make incorrect medical assessments.

TIPS

It is important to consider the possibility that differences in body awareness may be affecting how a patient recognizes or describes a symptom, or how a patient responds to illness. In some cases, you may need to do additional testing or imaging, because information from the history and physical examination may be limited.

Back to TopPlanning and Organizing

Consistency

Many individuals on the autism spectrum have a high need for consistency. They may become anxious or confused by changes in routine, which may lead to melt-downs or an inability to function. Alternatively, they may need more detailed explanations than other patients to plan for a visit or to stay focused and comfortable during a visit.

TIPS

You can get individualized information (e.g. via the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool) on strategies to address the need for consistency, but in general, the following strategies may be helpful to patients on the autism spectrum.

Before a visit, ask staff to do the following.

- Let the patient or his or her supporters know what is likely to happen during an office visit.

- If possible, avoid rescheduling appointments. Notify patients as soon as possible if the schedule changes unexpectedly.

- Give the patient pictures, or let the patient or a supporter take pictures, of the office or staff.

- When the patient checks in, let him or her know how long the wait is likely to be. Give patients plenty of warning if there is an unexpected delay.

Time awareness

Some individuals on the autism spectrum report difficulty with concepts related to time. This may make it challenging to answer questions about the onset, duration, or frequency of symptoms or illnesses. It may also make it more difficult to follow time-based instructions.

TIPS

- Help the patient answer questions about time by linking to important events in his or her life.

- Work with the patient to explain time-based recommendations. For example, help the patient set up an alarm for when to take a pill, or link the act of taking a pill to specific parts of a daily routine.

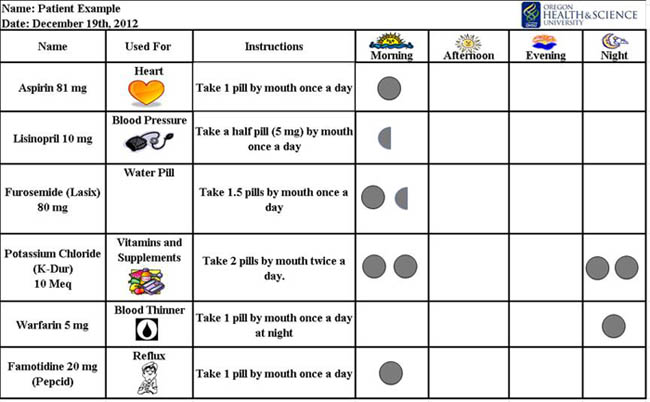

Visual thinking

Some but not all individuals on the autism spectrum "think in pictures". It may be easier for them to understand information and make decisions if you use visual aids. Note that patients with fluent speech may still have significantly stronger visual processing than auditory processing skills.

TIPS

- Offer to use diagrams, pictures, or models with patients who may benefit from them.

- Create (or have your staff or the patient's supporters create) visual schedules for your recommendations). Example:

Download a blank visual pill schedule (Excel)

Planning, organizing, and sequencing

Many individuals on the autism spectrum have difficulties with planning, organization, and sequencing. These challenges can have significant impacts on patients' ability to navigate the health system or follow recommendations.

TIPS

Possible accommodations or strategies to help minimize the impact of such challenges include the following.

- Write out detailed step-by-step instructions.

- Show patients what you want them to do while they are still in your office.

- Have office staff help the patient schedule follow-up visits, referrals, or tests.

- Show or have someone show the patient how to get to other places in your office or medical center.

- Have office staff contact the patient or his or her supporters after the visit, to make sure that the patient has been able to follow your instructions.

- Give patients worksheets or diaries to keep track of symptoms.

- Give the patient detailed information about how to communicate with office staff between visits.

Exams and Procedures

Physical examiniations, tests, and procedures

TIPS

It is best to obtain individualized information (e.g. via the Autism Healthcare Accommodations Tool) about what will help a patient better tolerate examinations of procedures. The following are examples of accommodations or strategies that may help patients.

- Explain what is going to be done before doing it.

- Show the patient equipment, or pictures of the equipment, before using it.

- If possible, let the patient do a "trial run" of difficult exams or procedures.

- Tell the patient how long an exam or procedure is likely to take.

- Warn the patient before touching or doing something to them.

- Limit the amount of time a patient must be undressed or in a gown.

- Give patients extra time to process things they need to see, hear, or feel before they respond.

- Allow the patient to sit, lie down, or lean on something during procedures, when possible.

- Let patients use a signal to tell you they need a break.

- Ask the patient from time to time if they are able to handle the pain or discomfort.

In many cases, thoughtful planning and appropriate accommodations can enable patients to tolerate examinations and procedures that have previously been intolerable. Nevertheless, there may be times when patients need anesthesia to tolerate examinations or procedures.

Phlebotomy

Phlebotomy may be particularly challenging for some patients on the autism spectrum. If a patient has had a particularly hard time with blood draws, you may consider some of the following strategies and accommodations.

TIPS

- Order blood tests only when absolutely necessary, and group them together to minimize the number of draws.

- Allow the patient to lie down or lean back on something.

- Use a numbing spray or cream.

- Be patient, and use a calm voice.

- Give the patient a very detailed explanation of what will happen, including how many tubes of blood you will fill.

- Consider giving the patient an anti-anxiety medication before the blood draw.

- Give the patient plenty of advance warning, so that they can prepare herself emotionally.

- Give the patient something to distract their attention.

Download Resources

PDF File Downloads

For alternate formats, contact info@aaspire.org